Chuck Evans’ MONTEZUMA Brand Sauces & Salsas pioneered the manufacture of chipotle pepper sauces and salsas in the United States. Chuck’s SMOKEY CHIPOTLE® Pepper Sauce and his SMOKEY CHIPOTLE® Salsa were the very first chipotle pepper sauce and salsa manufactured in the United States. Chuck has crafted an entire line of SMOKEY CHIPOTLE® sauces and salsas, including many varieties of chipotle salsas & salsa verde; chipotle barbecue sauces; chipotle shakertop seasonings, spices, & dry rubs; and chipotle pepper sauces.

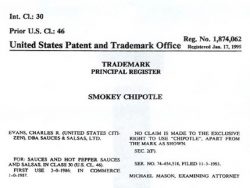

In January 1995, Chuck received the only trademark registration in the sauces and hot pepper sauces and salsas category, other than the McIlhenny Company’s Tabasco, for a variety name of chile and the first trademark incorporating the word chipotle.

In December 2007, after nearly 2 years of litigation, the United States Trademark Trial and Appeals Board upheld Chuck’s legal argument, which he authored, dismissing a competitor’s trademark counsel’s Petition for Cancellation challenging his SMOKEY CHIPOTLE® trademark. The Trademark Trial and Appeals Board dismissal with prejudice substantiates the validity and incontestable status of Chuck’s recognized trademark.

HOW “CHIPOTLE” GOT IT’S NAME…

The Spanish word “chipocle” and the more recent word “chilpotle”, meaning “smoked chile”, derived from the Náhuatl word tzilpoctli. Tzilpoctli combines tzilli meaning “chile” and poctli meaning “smoke”. Sometimes the Spanish translation “pochilli” is found in Mexican publications describing Cocina Prehispanica Mexicana (Pre-Hispanic Mexican Cooking). Other Náhuatl words used to describe smoked chile(s) are tzonchilli and texochilli.

The Mixtecas entrance into the Valley of Oaxaca, ca. 900 A.D., led to their occupation of the Zapotec capital of Monte Albán. The Toltecas of Central Mexico founded their capital of Tula north of the Valley of Mexico circa 980 A.D. and this cultural group of warrior traders conquered the Mayan Yucatán metropolis of Chichen Itza ca. 987 A.D., dominating much of Mesoamerica between 1000 A.D. to 1200 A.D. After the conquest of Maya region by the Spanish in 1541 A.D., present-day descendants of the Mayan language groups continue to occupy areas of Mesoamerica; including the Chiapas Highlands and the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. Direct descendants of the Mixtecas and Zapotecas have continually inhabited the Valley of Oaxaca.

Wandering tribes that spoke the same Náhuatl language migrated south to Central America from North America from a place called Aztlan, interpreted as “the place of the storks” or “of whiteness”. By circa 500 B.C., seven principal agricultural cultures had risen before the Mexicas arrival in the Valley of Mexico in the thirteenth century A.D. Civilizations appear to have emerged in Mesoamerica between circa 2000 B.C. and 1500 B.C. The “mother culture” Olmecas populated the humid lowlands of the Veracruz region of Mexico. Pre-Classic Maya thrived in city-states in southern Mexico, the Yucatán Peninsula, Belize, and the Petén rainforest in Guatemala and also in the highlands of Guatemala and El Salvador. The Maya of the Motaqua region was centered between lowland Quirigua in Guatemala and Copan in Honduras. The Zapotecas created the first great urban state, centered on the city of Monte Albán, founded in the valley of Oaxaca in southern Mexico. Early Teotihuacán valley inhabitants populated central Mexico. Teotihuacán and Monte Alban, powerful centers of early Mesoamerican civilization, traded extensively, however; maintaining a wary vigilance of the other.

Náhuatl was the language of the Mexicas, which included the nomadic Mesoamerican cultural group known as the Aztecas, a word coined by the Spaniards, for it is not found in the Náhuatl language. Around 1000 A.D., the Aztecas inhabited the region north of the Valley of Mexico which appeared to have been dominated and controlled by the Toltecas, a cultural group that maintained extensive trade networks and control over other regions of Mexico. As is known through historical sources, the Toltec civilization, whose capital city Tollan or Tula, began to suffer complacency, which led to internal dissension. Tribal cultural groups, including the Aztecas who had paid tribute to the Toltecas in the form of goods, services, and obedience, took advantage of this fact and began to liberate from Tula, which was destroyed circa 1165 A.D.

The Náhuatl word ‘tzilli’ derived from the Mayan word ‘tzir’ meaning picar-to be hot or irritar-to irritate.

In the semiarid land of Northern Arizona, survival of the westernmost Pueblo tribal community is dependent on accumulated knowledge of erratic weather patterns to insure plentiful crops. All Mesoamerican and Southwestern cultures including ancestors of the Hopis, were dependent upon successful harvests, and relied predominantly on maize (corn). Belief systems were dominated by appeasing deities representing weather and the need for rain to nourish arid fields.

With 12 villages located on First, Second, and Third Mesas, the Hopi practice religious ceremonies to secure help from supernatural forces believed to control nature. Present-day Pueblo tribal communities, including the Hopi, descended from the Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon cultures, circa 200 A.D. – 1300 A.D., commonly called Anasazi by the Diné (Navaho), meaning “Ancient Ones”. However, the Hopi believe that they are direct descendants of the Hisatsinom . . . “the ones who came before”.

The Hopi of Arizona; the Zuni of New Mexico; and to a lesser extent the Laguna and Acoma peoples of New Mexico (as well as limited participation from the other 16 recognized New Mexican Pueblo tribal communities); developed a complex religious pattern for mutual exchange of earthly goods that the supernaturals desired, for example: prayer feathers and corn pollen in exchange for favorable supernatural forces of weather and rain desired by the Hopi. This mutual exchange occurs during the yearly cycle of ceremonial dances by katsinas (kachinas), spiritual guardians of the Hopi way of life, and known as kokos in Zuni mythology, which are impersonated by the men of the villages. The Hopi and Zuni believe that all animate and inanimate objects possess a spirit; therefore, it is essential to preserve harmony with the world around them. Because so many circumstances require spiritual help, there are many katsinas in the Hopi pantheon. Likenesses of the guestimated 500 or so katsinum, (where 200-250 spiritual guardians may be current during the annual cycle), are carved out of cottonwood root and given as gifts to the Hopi children so that they can learn from the oral traditions of the katsinum cult. However, the Zuni frown on making likenesses of their kachinas available for sale to the public.

The Tsil Katsina is the Hopi Chili Pepper Katsina. It is interesting to note the similarity of the Mayan word ‘tzir’, and the later Náhuatl word ‘tzilli’, with tsil, the word for chile in the Uto-Aztecan language of the Hopi.

The Aztecas entered the Valley of Mexico ca. 1168 A.D., and in 1324 A.D. began to build Tenochtitlán (the center of present-day Mexico City) and the neighboring settlement of Tlatelolco around 1345 A.D. on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco. Fulfilling the mythical migration prophesy of their principal god Huitzilopoctli (Hummingbird on the Left) to pilgrimage south and settle on the spot where an Eagle is found with a snake in its mouth and perched on a cactus growing out of a rock (now the centerpiece of the present-day Mexican flag), a sacred enclave, known as the Great Temple (the Templo Mayor) was built to honor the ceremonial center of the Aztec Empire. After forming a Triple Alliance among Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tacuba settlements, the expansion of Azteca influence began by defeating the Tepanecas in 1428 A.D., conquering Tepanec settlements in the Valley of Mexico. For nearly the next one hundred years, the Aztec Empire dominated most of Mesoamerica from 1428 A.D. until the arrival of Hernan Cortès in 1519 A.D. In 1520 Moctezuma II was killed, and in 1521 A.D. after former disgruntled subjects of the Aztecs allied with the Conquistador, the city of Tenochtitlàn fell to the Spaniards.

The Spanish language combines the noun “chil”, meaning chile pepper, with “poctli”, the descriptive word humo, which en español, means smoke. “Chilpoctli”, subsequently refined to “chilpotle”, has culminated in the English translation “chipotle”.

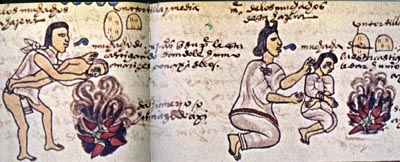

AZTEC PAINTED MANUSCRIPT…

Compiled circa 1541-42, the Codex Mendoza is one of the primary pictorial manuscripts depicting native society, economic organization, and history of the indigenous populace of Central Mexico before the fall of Tenochtitlán (present-day Mexico City). Commissioned during the administration of Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, it remains unknown whether the Spanish government initiated the project. The Codex consists of firsthand knowledge of pre-Conquest conditions. Colorful pictorial scenes were drawn on European paper by Mexica/Azteca scribes (tlacuilos) twenty years after the murder of Emperor Moctezuma II and the fall of the Aztec empire. The 71-page (plus title leaf) Codex Mendoza resides in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England.

Evidence of ripened red Chiles (which appear to be ripened Jalapeño peppers-note the broad shoulders and the tapered rounded-end typical of this variety of Capsicum Annuum), being smoked in the coals of a fire, is depicted in this scene from the Codex.

Where very few gringos north of the border knew just what a Chipotle was, Chuck created the rhythmic descriptive phrase SMOKEY CHIPOTLE. Before the turn of the 21st century (sounds like a long time ago, huh?) the adaptation of Chipotle Chiles as a natural smoky spice ingredient entered into our present culinary mainstream. Chuck’s descriptive phrase has simplified English-speaking understanding of the Chile Chipotle. In fact, Chile Chipotle is now a commonly used spice ingredient in many celebrity chef establishments, fusion-cuisine restaurants, Mexican grills, fast food operations, casual theme restaurants, sub sandwich shops, and rib joints.

Unlike most varieties of chiles, the ability to properly preserve the thick-fleshed Jalapeño cannot be accomplished by traditional air-drying under the sun. The Jalapeño was named after the ancient production center of Xalapa (Jalapa) in the state of Veracruz, The Jalapeño is also known as a Cuaresmeño, Gordo, or Huachinango in different growing regions of Mexico. The different varieties of the Chile Chipotle or Chile Ahumado, including the Típico, Meco, and it’s sibling Chile Morita (“little blackberry” or “little brown one”), a less costly smoke-imbued red-ripe Jalapeño, are commonly found in East-central and southern Mexican markets. Various chiles in Mexico are smoke-imbued, including the Pasilla de Oaxaca that is an ingredient in the famous mole negro. Smoked Chile Chipotles are also canned in adobo, imparting a rich smoky flavor to the simply-seasoned tomato sauce.

THE PEPPER PANTRY: CHIPOTLE is the definitive culinary study and recipe book about the Chile Chipotle.

Circa 1988-89, Chuck designed and custom-fabricated a stainless steel chile pepper press to make his seedless Smokey Chipotle® mash.